County War Agricultural Executive Committees (C.W.A.E.C.s) nationally

Bedfordshire Women's Land Army

>

Wartime Farming & Bedfordshire War

Agricultural Committee

War Agricultural Committees were formed immediately on the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939. Their members had been selected before the war and were appointed directly by the Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries. They were leading farmers and nurserymen, with a good knowledge of local conditions, who had volunteered, unpaid, to help in the campaign to get full production from the land in their particular county.

These Executive Committees, numbering eight to twelve members, predominantly

farmers, were given delegated powers by the Minister under the wartime Defence

Regulations. There was usually at least one landowner, one representative from

the farm workers and one woman representing the Womens Land Army. They formed

Sub-Committees to cover different aspects of work, and District Committees to

ensure that there was at least one Committee member in touch with every farmer,

up to say 50 or 60, in his area of 5000 acres. Later, some District Committees

embraced a representative from every parish. The role was to tell farmers what

was required of them in the way of wheat, potatoes, sugar beet or other priority

crops, and to help the farmers to get what they needed in the way of machinery,

fertilisers and so on to achieve the targets which were set them. They

administered, locally, various grant and subsidy schemes, the rationing of

feedstuffs and fertilisers and the provision of goods and services on credit.

predominantly

farmers, were given delegated powers by the Minister under the wartime Defence

Regulations. There was usually at least one landowner, one representative from

the farm workers and one woman representing the Womens Land Army. They formed

Sub-Committees to cover different aspects of work, and District Committees to

ensure that there was at least one Committee member in touch with every farmer,

up to say 50 or 60, in his area of 5000 acres. Later, some District Committees

embraced a representative from every parish. The role was to tell farmers what

was required of them in the way of wheat, potatoes, sugar beet or other priority

crops, and to help the farmers to get what they needed in the way of machinery,

fertilisers and so on to achieve the targets which were set them. They

administered, locally, various grant and subsidy schemes, the rationing of

feedstuffs and fertilisers and the provision of goods and services on credit.

The writer Laurie Lee, working for the Ministry of Information, summed this up in Land at War, the official story of British farming 1939 1944 (Her Majestys Stationery Office, 1945, p12) with the following simple example:

From Whitehall to every farm in the country the C.W.A.E.C.s formed a visible human chain which grew stronger with each year of the war. Here, roughly, is the way it worked. The Government might say to the Minister of Agriculture: We need so much home-grown food next year. The Minister assured himself that the labour, tractors, equipment, and so on, would be forthcoming, and said to the Chairman of a County Committee: Weve got to plough two million acres next year. The quota for your county is 40,000.

The Chairman said to his District Committee Chairman: Youve been scheduled for 5,000 acres.

The Committee-man said to his Parish Representative: Youve got to find 800 acres, then.

And the Parish Representative, who knew every yard of the valley, went to the farmer at the end of the lane.

Bob, he said, how about that 17.acre field for wheat?

And Farmer Bob said, Aye.

The Sub-Committees covered the following concerns: Cultivations, Labour, Machinery and Land Drainage, Technical Development, Feeding Stuffs, Insects and Pests, Horticulture, Financial and General Purposes, Goods and Services and War Damage.

The Committees employed paid officers such as the Executive Officer and assistants in each county and District Officers to keep the show running smoothly in every locality. Technical Officers were also employed to advise farmers about such matters as the lime requirements of their soils, the making of silage, the treatments of soil pests, the care of machinery and the improvement of livestock.

Bedfordshire WAEC Tractor Repair Depot, Bedford c.1940s

Farmers could get expert advice free, which contributed enormously to increase the output that farmers achieved.

Committees had their own Pest Destruction staff and where rats or rabbits had got too numerous, a team of trained land girls were employed to clear up the trouble. This became increasingly important as more and more corn was grown as one of the wartime priorities.

Threshing was another matter which the County Committees had to tackle. With so much corn being grown, steps had to be taken to organise threshing facilities in each county to ensure that farmers who did not have their own threshing machines got their corn threshed in a reasonable time. Each contractor had a definite zone of operation and was responsible for all the farms in a group of parishes, in such a way that cross journeys were avoided and each threshing team was kept fully employed.

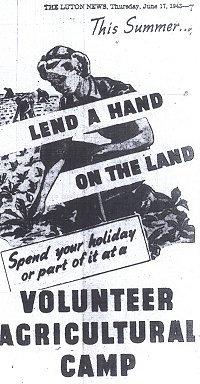

In addition to the supervision of work done by private farmers, the County

Committees, known colloquially as War Ags, farmed areas of land themselves,

particularly those farms and areas of derelict land which no individual was

willing to tackle properly. The clearing of derelict land and the drainage of

wet lands were two of those difficult jobs on which many land girls were

employed, particularly from 1942 onwards, when conscription brought in increased

numbers of young women members of the Womens Land Army. Many of these were

employed directly by the War Ags and housed, as mobile labour gangs, in

hostels located around each county. In addition, summer work camps set up by the

War Ags accommodated thousands of men and women, industrial and clerical

workers from Britains towns and cities, who volunteered to do paid work during

their summer holidays, to help bring in the harvest.

In addition to the supervision of work done by private farmers, the County

Committees, known colloquially as War Ags, farmed areas of land themselves,

particularly those farms and areas of derelict land which no individual was

willing to tackle properly. The clearing of derelict land and the drainage of

wet lands were two of those difficult jobs on which many land girls were

employed, particularly from 1942 onwards, when conscription brought in increased

numbers of young women members of the Womens Land Army. Many of these were

employed directly by the War Ags and housed, as mobile labour gangs, in

hostels located around each county. In addition, summer work camps set up by the

War Ags accommodated thousands of men and women, industrial and clerical

workers from Britains towns and cities, who volunteered to do paid work during

their summer holidays, to help bring in the harvest.

Nationally, there were fourteen Liaison Officers appointed by the Ministry of Agriculture to act as a link between the Committees, via a grouping of counties, and the Ministry in Whitehall, London. Control of cropping was vital if farmers were to produce what the Ministry of Food required. Many farmers, used to being independent and making their own decisions on what to farm, did not take kindly to being told what to do. For some, it meant a complete revolution regarding what they farmed. In some Midland counties there was not a plough or a man who knew how to plough before the war, since livestock and grass were their specialities. Others did not take kindly to having to grow potatoes.

The idea of having County War Ags was to make the task of mediating central dictates from national government more palatable by using well-respected local farmers to convey the war needs to farmers who knew them. Even so, when particular farmers failed to co-operate with this more democratic system, Orders were served on them requiring them to plough up their grassland, or to grow given acreages of various crops, to clean out their ditches and drains, or apply adequate quantities of fertilisers. In the worst cases, recalcitrant or incompetent farmers after first attempting to encourage and help them with advice and expertise could be removed from their farms, by the dictate of the Minister of Agriculture, and their land farmed by someone else who would use the land to better advantage.

To aid the farmers, War Ags set about introducing more and more machinery to facilitate the mass production of food now required by the war. Home production of tractors was greatly increased and machinery of all sorts from brought over from America, thanks to the Lend-Lease scheme, and from Canada, through Mutual Aid. They were distributed amongst the farmers, the dealers, and the machinery depots of the County Committees. Some of this machinery was quite novel for Britain the caterpillar tracked tractors and the first combined harvesters, which both cut and immediately threshed and bagged the corn in one mobile process. They cleared 36 feet in a single sweep, compared with the five-foot cut of the old horse-drawn binder. Training courses for both farmers and workers were needed, and for the mechanics who were to keep them going. Other machines were recognisable but much larger and more powerful than their predecessors.

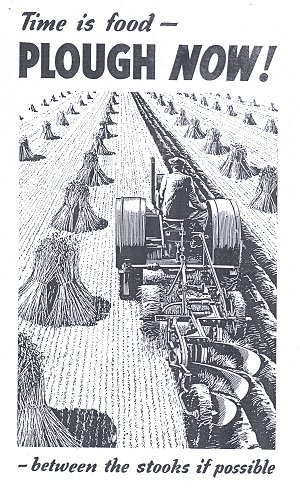

Night ploughing was introduced where it was the only way that the work could be completed on time. Shifts of workers operated as drivers so that tractors barely stopped for a minute, even when their drivers were having a break. One tractor did the work of many horses and men. Some plough-tractors were able to draw up to five furrows at a time and more speedily than previously. But horses, where they had been retained, continued to do their bit, and did not need the carefully rationed fuel required by engines.

Stuart Antrobus Historian/Author

Page last updated: 10th March 2014